FORTSETZUNG:DIE AUTOBIOGRAPHIE EMILL. FACKENHEIMS

Weitere Stellen aus dem Buch im Original, die die Schule in den dreißiger Jahre während der Nazizeit beschreiben. Hervorhebungen (Kursivschrift) stammen vom Autor. Auf S. 30f. lesen wir:

"Sometime, in 1934 ot 1935, all the students had to write on 'Why I am a National Socialist' - all except me, the only Jew. A fellow named Meier [Erg. B. Budnik: ELF schreibt den Namen falsch, gemeint ist Günter Meyer], who had never been known for political convictions, now wrote that he had always been a National Socialist, had always hated the Jews, and so on. The teacher, Jürgens's father, gave him a five, the worst mark. Old man Wenzlau was a good democrat, but no great hero: that he needed no courage to flunk Meier was proved by the sequel. The word about that essay got around. Somebody snatched it took it to the podium, and read it aloud while imitating Hitler in voice and gestures; getting into the fun, the other students kept shouting 'Sieg Heil'and giving the Hitler salute. While they carried on, the Nazis kept quiet: perhaps even Sporn was embarrassed by Meier's opportunism or, to use the appropriate German word his Anscheisserei. The rest of the students was disgusted. Thus it took no courage for me to walk over to Meier and announce that I was breaking off relations. Meier said that I was different, but I told him I did not want to be.

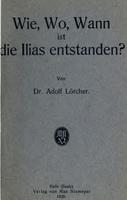

The way the Hitler salute was introduced is interesting. At first teachers just had to raise an arm, with some being more serious and some, such als Lörcher and Wenzlau, even Henkel, the music teacher, doing it wegwerfend, contemptously, thus producing laughter. Soon the Machthaber (rulers) had no choice but to dictate the words.

Another incident of that time stays with me, a competition on Turnen among the high schools of Halle. What with the HTV04 [Erg. B. Budnik: Hallescher Turnverein 1904] and my father's influence, I was good at high and parallel bars, so when the committee chose two youths to represent the Stadtgymnasium, my classmate Rossmann, the best Turner in the school, was the obious first choice, but they chose ma as second. At the competition I was so flustered, on the one hand, by the honor of representing the school, on the other, by doing it as a Jew, tha I messed up my exercise. People were nice about it, but I was disconsolate, my comfort being that Rossmann did not win either. Rossmann was a decent fellow. At age eighteen I won the Sportabzeichen, a medal for sport and Turnen. I looked forward to wearing it if only to impress the girls, but couldn't because it had a swastika; Rossmann was older and had obtained it before the Nazis got around th their swastika, so I asked him to swap medals, for it wouldn't matter to him. But Rossmann said he didn't want the damned thing either."

S. 34: " Evidently in my high school of 1933-1935 Jewish students such as I were protected by the remnant of an old-fashioned, conservative, if slightly anit-Semitic deceny, and my brother Wolfgang, who graduated a year afterward, found it still to be the case in 1936."

S. 35ff.: "The school's protective atmosphere prevailed until my graduation. Right to the end a small musical band kept meeting at our house, for my parents were known for their hispitality. (Or perhaps it was because nobody else had a set of drums.) Jürgen, of course, was one of the band; he played the violin, Herbert Thiess, a decent sort of whose politics, if he had any, I knew nothing, played the trumpet and the French horn. While I could play the piano, I played only the drums in the band, for Gustav Hennig, was the best pianist in the school.

Never in my life have I met a more unlikely Nazi than Gustav. An intellectual, absorbed in music and physics but nothing else, and miserable at sports, he was more like the Jew of caricature, altough he did not look like the stereotype. (I still have a picture of the band.) ... At matriculation, Gustav would have failed without me. Henkel, the music teacher, had used a great deal of Gustav's time, for his choir as well as for his orchestra. Now he felt obliged to push him through the matriculation, so he made me write the Greek exam for him and surreptitiously pass it on to Hennig.

I left the Stadtgymnasium in 1935 with a good feeling, for good reasons. With Greek the number one subject of both the school a myself, I passed the matriculation with the first lass honors., the only one in the class. Hence the old boys organization should have awarded their prize to me but, the year being 1935, they gave it instead to Jürgen, who had the highest B. Of course, they had no choice, and I knew it. But Hitler or no Hitler, some old boys protested against this discrimination, and a few even threatened to resign. Whether anyone did, I do not know.

My good feeling for the Stadtgymnasium, as for most things German, was destroyed by the Kristallnacht of November 9, 1938, and its sequels. My good feeling for Adolph Lörcher was never even threatened. Almost all my teachers were not Nazis and some were eveen anti-Nazi: Lörcher alone was steadfast, courageous, spelling it out. One day in the first week of July 1934 he stormed into class and verbally attacked Hitler. 'What Hitler did on June 30 he may never do again!' He meant that Hitler's actions were criminal and he should be toppled; but if Lörcher had said so explicitly, he would have been silenced, in one way or another, and he knew he must stay at his post. ...

Lörchger's war on Nazism was no one-time affair but was waged every single week, in religion class. In Germany religion was taught in school, and in Halle this meant Lutheranism. Jews and Catholics were exempt, and my class had one Catholic. The two of us usually stayed away, but when Lörcher taught, I attended voluntarily, for his teaching of Christianity was inseparable from war on Nazism, and he also invoked German patriotism. In years to come I had much cause to become anti-German as well as anti-Christian. But just by himself Adolph Lörcher made both impossible.

Lörcher taught religion, but his chief subject and love was Greek language, literature, and also, it came out toward the end, philosophy. His predecessor, a weary, nearly retired man named Reinecke - why, perversly, do I remember his name when I forget others I want to remeber - had announced de did not care whether we learned, for he got his salary anyway; and the result was that nobody learned. ... On leaving the Stadtgymnasium I still listed Greek philology, along with Jewish theology, as subjects for college study. Had there been no Hitler, might I have ended up as a classics professor at the Halle/Wittenberg Martin Luther University?

Im Kapitel 5 "Six Months of Collapse" (November 11, 1938 - May 12, 1939) kommt Emil L. Fackenheim noch einmal auf das Thema "Stadtgymnasium" zu sprechen. Auf S. 72 lesen wir:

"But Adoplh Lörcher phoned: he would never forgive me, he said, if I did not see him, so of course, I did. Lörher had two copies of Martin Buber's Königtum Gottes (Kingship of God), both inscribed dyoin tateron, 'one of two', a custom among 'classical' friends when they part. Then he said, 'I have always told you not to leave, that the Nazis disease must pass. Now you must leave; but you must promise me to come back, Germany will be destroyed' - by the Nazis, he meant, not by the English, Americans, Russians -' and we shall need to rebuild it.' I replied, 'Dr. Löcher, I have never contradicted you, but now I must.Two or three years ago, I might still have said 'I'll come back,' but now I know that Judaism and the Jewish people will need me more. Germany will have to be rebuilt, but by someone else.'

In 1999, after an honory doctorate at Martin Luther University Halle/Wittenberg, I asked the Stadtgymnasium for Lörcher's picture. They got me an article by him written long ago, but no picture; his name was no longer known in Halle." Auf dem nebenstehenden Kollegiumsfoto von Ostern 1920 ist - nach den Angaben auf der Rückseite des Fotos - Adolf Lörcher mit abgelichtet worden.

Wir werden versuchen, dem Wunsch Emil Fackenheims entsprechend nach einem Foto seines damaligen Lehrers Adolf Lörcher zu finden.

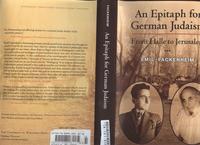

Quelle: "An Epitaph for German Judaism - From Halle to Jesusalem" von Emil L. Fackenheim, 2007, University of Wisconsin Press

****************************************************************************************************

Die Übersetzung aus dem Englischen von Auszügen aus dem Buch "Kein falsches Bild" von Frau v.Lips bzw. aus der englischsprachigen Autobiografie Emil L. Fackenheims kann - mit freundlicher Genehmigung von Erika Wielebinski - hier gedownloadet werden

****************************************************************************************************

[Bk 26-02-11]